Excerpts from Froissart's "Chronicles"

The Downfall of Richard II (1397-1400)

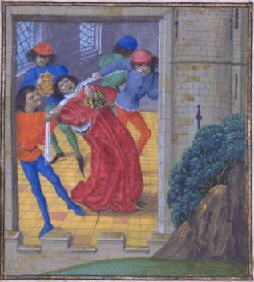

The Murder of Gloucester

Now I must say something about Thomas, Duke of Gloucester, the youngest son of King Edward III, in connexion with his constant and heartfelt dislike of the French. He was rather pleased than sorry to hear of the defeat which they had suffered in Hungary' and, having with him a knight called John Lackinghay, the chief and most intimate of his counsellors, he confided in him and said:

'Those frivolous French got themselves thoroughly smashed up in Hungary and Turkey. Foreign knights and squires who go and fight for them don't know what they are doing, they couldn't be worse advised. They are so over- brimming with conceit that they never bring any of their enterprises to a successful conclusion. That was proved often enough in the wars my royal father and my brother the Prince of Wales had with them. They could never capture a castle or win a battle against us. I don't know why we have this truce with them, for if we started the war again - and we have a perfectly good reason for doing so - we should make hay of them. Particularly at this moment, when all the best of their knights are dead or prisoners. And the people of this country want war. They can't live decently without it, peace is no good to them. By God, Lackinghay, if I live a couple of years longer in good health, the war will be renewed. I won't be bound by treaties and pacts and promises - the French never kept any of theirs in the past. They used fraud and trickery exactly as it suited them to steal back the domains in Aquitaine which had been made over to my royal father by an absolutely binding peace treaty. I pointed that out several times at the various meetings we had with them outside Calais. But they answered me in such smooth and flowery language that somehow they always managed to fall on their feet and I could never persuade the King or my brothers to believe me. Now, if there was a strong king in England today who really wanted a war to recover his rightful possessions, he could find a hundred thousand archers and six thousand men-at-arms all eager to follow him over the sea and risk everything in his service. But there isn't one. England hasn't a king who wants war or enjoys fighting. If she had, things would be different .....'

'I am the youngest of King Edward's sons,' the Duke of Gloucester went on, 'but if I was listened to I would be the first to renew the wars and put a stop to the encroachments we have suffered and are still suffering every day, thanks to our simplicity and slackness. I mean particularly the slackness of our leader the King, who has just allied himself by marriage with his principal enemy. That's hardly a sign that he wants to fight him. No, he's too fat in the arse and only interested in eating and drinking. That's no life for a fighting man, who ought to be hard and lean and bent on glory. I still remember my last campaign in France. I suppose I had two thousand lances and eight thousand archers with me. We sliced right through the kingdom of France, moving out and across from Calais, and we never found anyone who dared come out and fight us....'

'Things cannot go on like this,' the Duke continued. 'He's raising such heavy taxes from the merchants that they're growing restless, and no one knows where the money goes to. I know he spends plenty, but it's on silly and futile things, and his people have to pay the bill. There will soon be serious trouble in this country. The people are beginning to grumble and say that they won't stand it much longer. He's letting it be known, since there is a truce now with France, that he thinks of leading an expedition to Ireland and employing his knights and archers that way. He's been there before and gained very little, for Ireland is not a place where there's anything worth winning. The Irish are a poor and nasty people, with a miserable country that is quite uninhabitable.'

'Even if the whole of it were conquered one year, they'd get it back the next. Yes, my good Lackinghay, all that I'm telling you is absolute fact.'

In conversation with his knight, the Duke of Gloucester used foolish words like these, and others still worse, as was disclosed later. He had conceived such a hatred for the King that he could find nothing to say in his favour. In spite of the fact that, with his brother, the Duke of Lancaster, he was the greatest man in England and ought to have taken a leading part in the government of the realm, he showed no interest in it. When the King sent for him, he went if it suited him, but more often he stayed away. If he did go, he was the last to arrive and the first to leave. As soon as he had given his opinion, he insisted on its being accepted without question, then took his leave immediately and mounted his horse to ride back to Pleshey, a place in Essex thirty miles from London where he owned a fine castle. It was there that he spent most of his time.

The Duke worked in all kinds of subtle and secret ways to win over the Londoners to him, feeling that, if he had them on his side, the rest of England would be his also. He had a great-nephew, the son of the daughter of an elder brother of his called Lionel, who had been Duke of Clarence and had been married in Lombardy to the daughter of Galeazzo, Lord of Milan, and had died at Asti in Piedmont. The Duke of Gloucester would have liked to see this great-nephew of his, whose name was John, Earl of March, on the throne of England, in place of King Richard, who he said was unworthy to reign. He made this clear to those in whom he was rash enough to confide and he arranged for the Earl of March to come and visit him. When he was there, he revealed all his most secret ambitions to him, saying that he himself had been chosen to appoint a new king for England and that Richard would be shut up, and his wife with him. There would be sufficient provision for their eating and drinking as long as they lived. He entreated the Earl of March to agree to this and to rely on his word, saying that he could make it good and that he already had the support of the Earl of Arundel, Sir William and Sir John Arundel, the Earl of Warwick and numerous other barons and prelates.

The proposition dismays the young Earl of March, but he prevaricates, saying he needs time to think it over. Having sworn to observe secrecy, he leaves for Ireland and has no more dealings with Gloucester.

The Duke then stirs up the merchants of London, urging them to ask to be relieved of taxation originally imposed to meet the expenses of the wars, but now squandered on King Richard's entertainments. Together with the councillors of several other towns, they petition the King for relief but are temporarily placated by the Dukes of York and Lancaster, and summoned to attend a parliament at Westminster. Here again, Lancaster speaks for the King:

'It is my Sovereign's pleasure, men of London, that I should reply specifically to your demands, and I do this on the instructions of the King and his council and in accordance with the will of the prelates and nobility of his realm. You are aware that, in order to avert greater evils and provide safeguards against certain dangers, it was decided and unanimously agreed by you and the councils of all the cities and large towns in England that a tax of thirteen per cent should be levied on sellers of goods - in the form which has now been current for about six years.

'In consideration of this the King granted you a number of concessions, which he does not wish to withdraw, but on the contrary increase and amplify progressively, provided you are deserving of them. But should you prove rebellious and refractory to an undertaking which you willingly entered into, he annuls everything he has conceded. And here present are the nobles, prelates and holders of fiefs, bound by oath to the King, and he to them, to aid each other mutually in the maintenance of all measures lawfully decreed and established in the best interests of all, to the execution of which oath they have subscribed in full knowledge. Take note of this and remember that the King's establishment is large and powerful. If it has increased in some ways, it has diminished in others. His rents and other sources of revenue yield him less than in the past, and he and his officers had to bear heavy expenses when war was renewed with France. Then great expenditure was incurred by the emissaries who went over to negotiate with the French. The preliminaries to the King's marriage have also been very costly. And, although there is now a truce between the two countries, much money has to be spent on the garrisons of the castles and towns which owe allegiance to the King, whether in Gascony or the districts of Bordeaux, Bayonne and Bigorre, or those of Guines and Calais, as well as all our coastal area, which has to be guarded with its ports and havens.

'On the other side, the whole of the Scottish border, with its roads and passes, requires guarding, and so does the frontier in Ireland, which is a lengthy one. All these things and many others relating to the royal establishment and the prestige of England cost large sums of money every year. The nobles and prelates of the realm know and understand this better than you, who are busy with your manufacturing and your merchandizing. Be thankful that you have peace and remember that no one pays unless he has the means and is doing business. Foreigners have to pay considerably more than you in this country. You get off much more lightly than they do in France and Lombardy and other places to which quite possibly you send your goods, for they are taxed and re-taxed two or three times a year, while you are subject to a reasonable assessment based on the amount of trade you do.'

The London merchants meekly submit. The Duke of Gloucester, who has attended the parliament, keeps silent and returns to his seat at Pleshey.

Soon after, the Comte de Saint-Pol arrives from France on a good-will mission to Richard and his infant queen. Informed of the dangers threatening the King, he advises him to take action before it is too late.

I was informed that, about a month after the Count of Saint-Pol had returned to France, a report spread through England which was highly detrimental to the King. The general rumour was that the Count had come over to discuss some way of giving Calais back to the French. No single question could have disturbed the English people more thoroughly than this. The consequence was that the Londoners went to see the Duke of Gloucester at Pleshey. The Duke neither calmed them nor denied the rumours, but made the most he could of them by saying: 'It's extremely likely. The French wouldn't mind if he took all their King's daughters, provided they became masters of calais.'

Depressed by this reply, the Londoners said that they would go and speak to the King and tell him squarely how disturbed opinion was. 'Certainly,' said the Duke. 'Speak out loud and pointedly, and don't be shy about it. Listen carefully to what he says in reply and then you will be able to tell me about it when I next see you. I will advise you according to the answer he gives. It's highly probable that some crooked business is afoot. The Earl Marshal, who is captain and governor of Calais, has already been twice into France and stayed in Paris, and he had more to do with arranging the marriage with the French King's daughter than anyone else. The French are very clever at laying their plans far ahead and slowly nearing their aim. And they give big promises and rewards if it helps them to gain their ends.

With the Duke's encouragement, the men of London went one day to Eltham to see the King. With him at that time were his two half-brothers, the Earls of Kent and Huntingdon, the Earl of Salisbury, the Archbishop of Canterbury, his confessor the Archbishop of Dublin, Sir Thomas Percy, Sir William de Lisle, Sir Richard Credon, Sir John Golafre and several knights of his household. The Londoners explained the reason for their visit, putting it in very respectful and temperate terms, and they told him of the scandalous rumour which was spreading through England.

The King assures them that Saint-Pol's visit was a purely friendly one, with no ulterior motive. Lord Salisbury also speaks out to condemn the disseminators of idle rumours. These could easily lead to a popular rising, with harmful consequences for them all. Largely reassured, the Londoners Leave, but Richard remains shaken by the episode and begins to distrust all his Uncles, though his chief fear is of Gloucester. Soon after, he receives information, considered reliable, of the plot to the Queen and himself and put them under guard. The country is to be governed temporarily by Lancaster, York, Gloucester and Arundel each taking a different region. A pretext is to be found for ending the truce with France and for sending the infant Queen back to her father if she so chooses.

If the King of France wished to have his daughter back, she was still very young and aged only eight and a half, so she could well wait until she reached womanhood. When she was twelve she might quite possibly regret her marriage, for she had been married to Richard in all innocence, and it had been an unjust step to break off her match with the heir of Brittany. If, however, she chose to stay and observe the present marriage arrangements, she would remain Queen of England and would have her dowry. But she should never be deflowered by the King of England; and, if he died before she reached the age, they would examine the question of sending her back to France.

Unrest grows in the country, and with it Richard's anxiety. He appeals to his uncles of Lancaster and York to give him their advice and support.

They said to him: 'Sire, be patient and leave things to time. We know that our brother Gloucester is the most Unruly man in England, and the rashest. But he is only one man and can achieve nothing by himself. If he is working on one side, we will work on the other. As long as you will allow us to advise you, you will take no notice of our brother. He sometimes says all kinds of things which are quite baseless. He alone, or his intimates, cannot break the truce with France, and as for shutting you up in a castle or separating you from your wife, the Queen, we will never allow such things to happen. He is deluding himself when he talks in that way. So be reassured, matters will right themselves. What one sometimes thinks or says is not the same as what one actually does.'

With such arguments the Dukes of Lancaster and York calmed their nephew Richard of England.

Seeing, however, that the affairs of the realm were be- ginning to go badly 2nd that a great feud was growing up between the King and Gloucester, they did not wish to be involved. Taking leave of the King for a time, they left the court with the whole of their families and withdrew each to his own place. The Duke of Lancaster took his wife, Catherine Ruet, who for some time had been a companion to the young Queen, and took the opportunity to go hunting stags and deer, as the custom is in England. The King remained with his followers in the London region. Later his two uncles bitterly regretted having left him, for soon after their departure things happened which caused deep disquiet in the whole of England and which would not have occurred if they had stayed. They would have given very different advice from that which the King now received from his followers.

Richard's intimates work on his fear of Gloucester, which some of them share. They stress the charges brought against him by Popular rumour, particularly those of being a weak and cowardly sovereign.

King Richard noted all these things which were said to him in the privacy of his chamber and took them so much to heart (he was apprehensive by nature) that, shortly after the Duke of Lancaster and York had gone away, he decided upon a bold and daring move. He had reflected that it was better to destroy than to be destroyed and that speedy action could prevent his uncle from ever being a threat to him again. Since he could not carry out his plans without help, he confided in the man whom he trusted most, his cousin the Earl Marshal, Earl of Nottingham, telling him exactly what he wanted done. The Earl Marshal, who preferred the King to the Duke of Gloucester, having received many favours from him, revealed the King's plans to no one, except to those whose assistance he required, for he also could not act alone. What had been agreed between them will become clear as you read on.

On the pretext of hunting deer, the King went to a manor in Essex called Havering-atte-Bower, twenty miles from London and about the same distance from Pleshey, where the Duke now lived almost permanently. One afternoon the King left Havering-atte-Bower with only a part of his retinue, having left the others at Eltham with the Queen, and reached Pleshey at about five o'clock. It was a very fine, hot day with no one keeping watch, and he entered the castle unnoticed, until someone shouted: 'The King is here !' The Duke of Gloucester had already finished supper, for he was a sparing eater and did not linger over his meals. He came out to meet the King in the courtyard of the castle, receiving him with all the forms of respect due to the sovereign, which he well knew how to pay. The Duchess and her children who were there did the same. Then the King went into the hall and from there into the chamber. A table was set for him and he ate a little. He had already said to the Duke: 'Uncle, have some of your horses saddled - not all, but half-a-dozen - I want you to come back to London with me. I have a meeting with the Londoners tomorrow at which my uncles of Lancaster and York will certainly be present, and I shall want your advice on how to deal with a request they are bringing to me. Tell your steward that the rest of your people must follow tomorrow and join you in London then.'

The Duke, who had no suspicions, readily agreed. The King soon finished eating and got up. Everyone was ready; the King took leave of the Duchess and her children and mounted his horse, as did the Duke, taking with him from Pleshey only four squires and four servants. They took the Bondelay road to have an easier ride and avoid Brentwood and other towns and they travelled fast, for the King pretended to be in a hurry to reach London. He and his uncle chatted together as they rode and made such progress that soon they came near to Stratford and the Thames. There, in a narrow place, the Earl Marshal was waiting in ambush. When the King had almost reached the spot, he left his uncle's side and galloped ahead of him. The Earl Marshal appeared with a number of men on horseback and, going up to the Duke of Gloucester, said: 'I arrest you in the King's name.' The Duke was astounded and saw clearly that he had been betrayed and began to shout after the King....

Richard, on whose orders all this was being done, affected not to hear, but rode straight on and came that night to the Tower of London.

His uncle of Gloucester had a very different lodging, for in spite of his protests, he was forced into a barge on the Thames and transferred from that to a ship which lay at anchor in the middle of the river. The Earl Marshal and his men also went on board and they sailed down the river, reaching Calais late the next day with the help of a following wind. Only the King's officers in Calais, of which the Earl Marshal was the governor, knew about their arrival....

Early the next morning the King left the Tower of London for Eltham, where he remained. In the evening of the same day the Earls of Arundel and Warwick were taken to the Tower and imprisoned there, to the amazement of London and the rest of England. Many strong protests were raised, but no one dared to go against the King's orders for fear of incurring his anger.

The people console themselves with the thought that Lancaster and York will restrain the King. Meanwhile, the Duchess of Gloucester has appealed directly to the two dukes. They send her reassuring answers and remain passive.

When the Duke of Gloucester had been taken into the castle of Calais and found himself shut in there and deprived of his attendants, he began to feel very afraid. He said to the Earl Marshal: 'Why have I been spirited out of England and brought here? You seem to be treating me as a prisoner. Let me take a walk through the town and see the fortifications and the people and the sentries.' 'Sir,' replied the Earl Marshal, 'I dare not do as you ask, for my life is answerable for your safe-keeping. My lord the King is a little displeased with you at the moment. He wishes you to stay here and put up with our company for a time. You will do that until I receive further instructions, which I hope will be soon. As for your own displeasure, I am very sorry about it and I wish I could relieve it. But I have my oath to the King, which I am bound in honour to obey.'

That was all the Duke could get from him and concluding, from other signs that he noticed one day, that his life was in danger, he asked a priest who had already sung mass for him to hear his confession. He confessed at some length, kneeling before the altar in a pious frame of mind, devout and contrite. He prayed and asked God's mercy for all the things he had done and repented of all his sins. It was indeed high time for him to purge his conscience, for death was even nearer to him than he thought.

According to my information, just at the hour when the tables were laid for dinner in the castle of Calais and he was about to wash his hands, four men rushed out from a room and, twisting a towel round his neck, pulled so hard on the two ends that he staggered to the floor. There they finished strangling him, closed his eyes and carried him, now dead, to a bed on which they undressed his body. They placed him between two sheets, put a pillow under his head and covered him with fur mantles. Leaving the room, they went back into the hall, ready primed with their story, and said this: that the Duke had had an apoplectic fit while he was washing his hands and had been carried to his bed with great difficulty. This version was given out in the castle and the town. Some believed it, but others not.

Two days later, Gloucester is reported to be dead. The Earl Marshal and all the English officers in Calais put on mourning. The reaction in France is one of relief. In England, opinions are divided.

After the Duke's death at Calais, he was given an honourable embalmment and put in a lead coffin with a wooden casing and so sent by sea to England. The ship carrying him anchored under Hadleigh castle, on the Thames, and from there the body was conveyed very simply to Pleshey and placed in the church of the Holy Trinity which the Duke himself had founded, appointing twelve canons to perform the divine services; and there he was buried.

It may be said that the Duchess of Gloucester, with her son Humphrey and her two daughters, were naturally deeply distressed when their husband and father was brought home dead, and the Duchess had to suffer another blow when the King had her uncle, Earl Richard of Arundel, publicly beheaded in Cheapside, London. None of the great barons dared to thwart the King or dissuade him from doing this. King Richard was present at the execution and it was carried out by the Earl Marshal, who was married to Lord Arundel's daughter and who himself blindfolded him.

The Earl of Warwick was in great danger of being beheaded also, but the Earl of Salisbury, who was high in the King's favour, interceded for him, as did other nobles and prelates, with such strong arguments that the King granted their request.

Warwick is reprieved, on Salisbury's plea, and banished for life to a comfortable exile in the Isle of Wight. The Dukes of Lancaster and York, highly alarmed by the death of their brother Gloucester, now bestir themselves and come to London.

At that date King Richard, who was established at Eltham, summoned to him all those who held fiefs from him and owed him homage. He assembled and maintained more than ten thousand archers round London and in the counties of Kent and Sussex. He had with him his half-brother, Sir John Holland, the Earl Marshal, the Earl of Salisbury and many of the English knights and barons, and he sent orders to the Londoners that they were not to harbour the Duke of Lancaster. They replied that they knew nothing against the Duke to make him unacceptable. Lancaster therefore remained in London, with his son the Earl of Derby, and also the Duke of York, whose son, the Earl of Rutland, was on intimate terms with the King. With the Earl Marshal, the King loved him beyond reason.

Rutland mediates between King Richard and Lancaster, who reflects that a breach with Richard and hence with the French, who would support him, might prove harmful to his two daughters, who are married to the Kings of Spain and Portugal. He is persuaded grudgingly to make peace with Richard and receives his promise to act in future only on his advice. The promise is never observed.

So King Richard was reconciled with his uncles over the death of the Duke of Gloucester and went on to rule more harshly than before. He moved his establishment to Essex, formerly the domain of the Duke of Gloucester and which ought to have gone to his heir, Humphrey. But the King took freehold possession of it all. The rule in England is that the King has custody of the inheritances of all minors who lose their fathers and that the inheritances are returned to them when they are twenty-one. King Richard made himself the trustee of his young cousin, Gloucester's heir, and took over all his lands and possessions for his own benefit. He obliged young Humphrey to live in his household, and the Duchess and her two daughters in that of the Queen. He removed from Humphrey the hereditary office of Constable of England, which his father had held in his lifetime, and gave it to his cousin the Earl of Rutland. He began to reign with greater pomp than any English king before him; none had come within a hundred thousand nobles yearly of the amount he now spent. He likewise brought to his court the heir of the Earl of Arundel, whom he had had beheaded in London, as already related. Because one of the Duke of Gloucester's knights called Corbet spoke too freely one day about the King and his council, he had him seized and beheaded. Sir John Lackinghay was also in great danger, but when he saw that things were going against him, he tried to put a smooth face on it, left the service of his lady the Duchess of Gloucester, and went to live elsewhere.

In those days, not even the greatest in England dared to criticize the King's acts or intentions. He had his private circle of advisers, the knights of his chamber, who persuaded him to do everything they wanted And the King kept in his pay a retinue of two thousand archers who guarded him day and night, for he felt by no means safe from his uncles or from the family of the Earl of Arundel.

The Challenge and Bolingbroke's Banishment

It was only too true that the Duke of Gloucester's death had greatly disturbed several of the great lords of England, some of whom talked and complained confidentially among themselves. But the King had so subdued them that none dared to show his dissatisfaction openly, for Richard had had the word spread throughout England that anyone who spoke in favour of either the Duke of Gloucester or the Earl of Arundel would be branded as false, miscreant and a traitor and would incur his extreme anger. Such threats had imposed silence on many people who were in strong disagreement with his recent actions.

In these circumstances the Earl of Derby and the Earl Marshal were having a conversation on various matters and, from one thing to another, came to speaking about the King and his council in which he placed so much trust. The Earl Marshal took particular notice of a remark made with the best intentions by the Earl of Derby, who meant it as a confidential opinion and never thought that it would be repeated. There was nothing disloyal or excessive about his words, which were these: 'Well, good cousin, what does our cousin the King think he is doing? Does he want to drive all the nobles out of England? There will be none left soon. He shows clearly that he has no desire to increase his country's power.' The Earl Marshal made no reply, but affected to ignore a remark which he thought was highly offensive to the King. However, he could not keep it to himself, feeling that the Earl of Derby was on the point of stirring up trouble in England, with the support of the Londoners who loved him greatly. He decided - since the devil was no doubt working on his mind and what must be, must be - that the Earl of Derby's words must be repeated to the King in such a public way, and in the presence of so many of the nobility, that an open scandal would be unavoidable. So soon afterwards he went to the King and, thinking to please him and enter his good graces, he said: 'My lord, all your enemies and illwishers are not yet dead or out of England.' 'What do you mean by that, cousin?' said the King, changing colour. 'I know what I mean,' replied the Earl Marshal, 'but for the moment I will say no more. But in order to deal promptly and effectively with the matter, you should hold a solemn feast this coming Easter and summon to it all the members of your family who are in England, not forgetting to invite the Earl of Derby, and then you will hear some very peculiar things which you do not suspect at present. They touch you closely.'

The King became very thoughtful when he heard this and asked the Earl Marshal to be more explicit, assuring him that whatever he told him would remain secret. I do not know whether he said more then, but if he did the King gave no outward sign of it and allowed the Earl Marshal to proceed with his intention, with the results which I will describe. The King announced a solemn festival at Eltham, to be held on Palm Sunday, to which all his kindred were invited. He particularly urged his uncles of Lancaster and York to come with their children, and they, suspecting nothing amiss, appeared with their full retinues.

After dinner on the day of the festival the King retired to his robing-room with his uncles and the other nobles. He had not been there long when the Earl Marshal, his plan fully prepared, came and knelt before him, saying: 'Beloved sire and mighty King, I am your kinsman and liegeman and Marshal of England I am closely bound to you by word and oath. I have sworn with my hand in yours never to be in any place or company where evil is spoken against your royal majesty. If I were, and concealed it in any way whatsoever, I would rightly be called false, miscreant and a traitor,' which thing I will never tolerate, but rather will do my duty to you in all circumstances.'

The King looked at him fixedly and said: 'Why do you say this, Earl Marshal? We wish to know.'

'My very dear and mighty lord,' replied the Earl, 'I will tell you because I cannot suffer or conceal a thing which may be prejudicial to you. Call out the Earl of Derby and I will speak openly.' The Earl of Derby was called forward by the King, and the Earl Marshal, who had spoken on his knees, was told to stand up.

When the Earl of Derby had come forward in all innocence, the Earl Marshal said to him:

'Lord Derby, I maintain that you thought and spoke what you ought not to have done against your natural lord and master, the King of England, in saying that he is unworthy of ruling land or kingdom, since without forms of justice or consultation with his men, he unsettles his realm and with no shadow of justification drives out from it the gallant men who would help him to protect and uphold it: wherefore I offer you my gage and am ready to prove by my body against yours that you are false, miscreant and a traitor.'

The Earl of Derby was astounded by these words and drew back, standing very stiffly for some time without speaking or consulting his father or his men on what he ought to say in reply. When he had reflected a little, he stepped forward with his hat in his hand and, coming before the King and the Earl Marshal, he said: 'Earl Marshal, I say that you are false, miscreant and a traitor. All that I will prove by my body against yours and here is my glove.' Upon which the Earl Marshal, noting the challenge and being clearly willing to fight the Earl, picked up the glove and said: 'Lord Derby, I call the King and all these lords to witness your words. I shall turn your word to derision and prove mine true.'

Both earls then drew back among their followers; the ceremony of serving wine and sweetmeats was abandoned, for the King showed signs of extreme displeasure. He went into his private room and shut himself in there. His two uncles remained outside with all their children and the Earls of Salisbury and Huntingdon. Shortly afterwards the King called the last two in to him and asked them what was the best thing to do. They answered, 'Sire, send for your Constable and then we will tell you.' The Earl of Rutland, Constable of England, was summoned and, when he entered, was told: 'Constable, go out to the Earl of Derby and the Earl Marshal, and make them give assurances that neither will leave England without the King's permission.' The Constable did as he was instructed, then went back to the King's room.

As you can well imagine, the whole court was in a state of confusion and many of the nobles and knights were greatly disturbed, privately blaming the Earl Marshal. But he could not take back what he had said and he appeared to have no thought of doing so. He was far too great and haughty, with a heart full of pride and presumption. So the various lords left, each returning to his own house.

The Duke of Lancaster, though outwardly calm, was greatly upset by the words that had been exchanged. He felt that the King ought not to have taken them in the way he did, but should have passed them over. This was also the opinion of the majority of the English barons. The Earl of Derby took up his residence in London, where he had his palace. His guarantors were his father, his uncle the Duke of York, the Earl of Northumberland and many other prominent lords, for he was greatly liked in England. The Earl Marshal was sent to the Tower of London and took up residence there, and the two earls made lavish preparations for the combat. Lord Derby sent messengers urgently to the Duke of Milan in Lombardy to obtain armour of his size and choice. The Duke welcomed his request and allowed a knight whom the Earl had sent, a certain Sir Francis, to make a choice among his entire collection of armour. Not content with that, after the knight had inspected the plate and mail and picked out all the pieces he wanted, the Duke of Milan, inspired by sheer generosity and the desire to please the Earl, sent four of the best armourers in Lombardy back to England with the knight to ensure that the Earl of Derby was fitted to his exact size. The Earl Marshal, for his part, sent to places in Germany, where he thought his friends would help him and defray his expenses, and he also equipped himself lavishly for the day. The whole business proved very costly to the two noblemen, each striving to outdo the other. In particular, the Earl of Derby spent much more on his preparations than the Earl Marshal on his. I must say that, when the Earl Marshal first embarked on the affair, he expected stronger support and assistance from the King than he received. But those who were near to Richard advised him thus: Sire, you should not intervene too openly in this business. Say nothing and let them get on with it; they will manage all right. The Earl of Derby is extraordinarily popular in this country, especially among the Londoners, and if they saw you taking sides with the Earl Marshal against him, you would lose their favour entirely.' King Richard saw the force of these arguments and realized that they were sound. He therefore hid his hand as far as he could and left the two to provide themselves with arms and trappings on their own account.

Nevertheless, public opinion is critical of Richard's inaction. It is felt that he should have used his authority to stifle the affair. Lancaster deplores the matter in private but is too proud to approach the King, since his son's honour is involved. The Londoners and some of the nobles express their strong support of Derby, saying that he has a better. claim to the throne than Richard, who was imposed upon them by his grandfather, Edward III Richard again consults his inner council and receives advice which he proceeds to follow.

A short time after the King had held this council, he summoned many of the prelates and great barons of England to Eltham. When they were assembled, he acted on the advice he had been given and called before him the Dukes of Lancaster and York, the Earls of Northumberland and Salisbury, his half-brother the Earl of Huntingdon, and the other great lords of his kingdom who had come to witness the combat. The Earl of Derby and the Earl Marshal were at Eltham also, each with his followers and an apartment of his own. They were forbidden to meet, the King letting it be known that he wished to stand between them and that he was highly displeased by all they had said and done, which were not things to be easily forgiven. He then sent the Constable and the Steward of England with four other noblemen to obtain a promise from the two adversaries that they would obey any order that the King gave them. Both pledged themselves to do so and their promise was reported to the King in the presence of the whole court. The King then said:

'I proclaim and command that the Earl Marshal, on the grounds that he has sown dissension in this country and uttered words of which there is no other evidence but his own account of them, shall put his affairs in order and leave the kingdom for any place or land where he pleases to live, this banishment being perpetual with no hope of return. Next, I proclaim and command that our cousin the Earl of Derby, on the grounds that he has angered us and is in some part the cause of the Earl Marshal's offence and punishment, shall prepare to leave the kingdom within fifteen days and go to whatever place he chooses. The length of his banishment is ten years, unless we recall him. In his case we may exercise our power of recall or remission at any time which may seem good to us.'

This sentence was received with fair satisfaction by the lords who were present.

The Earl Marshal having banked funds for his use with the Lombards in Bruges, leaves for Calais, of which he had once been the governor. From there he makes his way to Cologne. Derby takes formal leave of the King, who remits four, years of his exile as had previously been planned. Amid the lamentations of the citizens of London, he also leaves for Calais. Declining the invitation of the Count of Ostrevant to come to Hainault, he goes on to Paris, where he is welcomed by the French royal Family. In February 1399, his father dies. Far from taking this opportunity to recall and pardon him, Richard seizes the Lancastrian estates. This makes little difference to the favour which Derby enjoys in France.

As a matter of fact, the King of France never for a moment had unfavourable thoughts about him, and neither had his brother or his uncles. They had great love and respect for the Earl of Derby and wanted to have him with them even more; and very good company he was to them. They considered the point that he was a widower and free to re-marry, and that the Duke of Berry had a daughter, already widowed twice but still young, called Marie. She had been married to Louis de Blois, who had died young, and then to Lord Philip of Artois, Count of Eu, who had died on the way back from Hungary. Marie de Berry would have been about twenty-three at that date. Her marriage with the Earl of Derby had been considered and negotiated and was on the point of being concluded, for it was well known that the Earl was heir to great estates in England. Moreover, the King of France was influenced by the thought of his daughter, the young Queen of England. It was felt by him and other French lords that two great ladies such as they were and so closely related would be excellent company for each other, and also that the marriage would draw the two countries closer in peace arid friendship. Those who held this opinion were quite right, but the match came to nothing. It was fated to be broken off, thanks to the intervention of King Richard and his council.

Richard sends the Earl of Salisbury to Paris to inform the French of his displeasure at the prospect. The marriage project is dropped.